Myofascial Release Therapy

I propose that the primary mechanism behind myofascial release therapy is its influence on the central nervous system rather than the fascial system itself. Any improvements in wellness resulting from this therapy are likely due to a neurological response to touch rather than direct manipulation of fascia. While other systems of the body may experience benefits from myofascial release, these are indirect effects stemming from the nervous system’s response.

When the nervous system is soothed, it can lead to activation of the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system, promoting relaxation and improved function across other systems. Thus, the claims that myofascial release directly influences fascia are less relevant. If a client believes the therapy is effective, the placebo effect can play a significant role in reducing pain.

Additionally, fascial therapies may provide psychological and sociocultural benefits, which are vital in pain management, as supported by the biopsychosocial model of pain. This model highlights the interplay between biological, psychological, and social factors in the experience and management of pain. Myofascial release, therefore, may contribute to pain relief not through direct structural changes to fascia, but via neurological, psychological, and social mechanisms.

Mechanisms of Myofascial Release Therapy

What is a Placebo?

When I speak to my clients, I often say that pain is in their brains, but I quickly follow up with the statement that there is no switch inside their heads to turn off the pain. Telling them this is crucial because I don’t want them to think I am belittling their experience; your pain is real, and I don’t need proof to trust your assessment.

The brain is a magnificent machine that does all sorts of wonderful things. The more we learn about how it works, the better we become at managing our pain and living our best lives.

Placebo is a beautiful mechanism of the brain, and it can be invaluable in the treatment of pain. Sometimes, we need to believe something is happening so our brain stops interpreting nociceptive signals as pain.

What is placebo? A placebo is an inactive, harmless substance, sham intervention, or mock procedure that can help patients feel better through the power of suggestion. Physicians have used placebos to treat patients’ symptoms without exposing them to potential adverse effects of pharmacological or surgical interventions. The improvement a patient experiences may be related to an anticipation that the product will work. It is important to note that the placebo effect typically occurs in subjective responses, such as nausea and pain, rather than objective ones, like wound healing. [2]

A blind study published in 2002 discussed the efficacy of arthroscopic surgery for knee osteoarthritis, comparing actual procedures with placebo surgery. The results of this trial revealed that the surgery was no more effective at relieving pain than a sham procedure. [3] While the study mainly focuses on the weak efficacy of arthroscopic surgery for the knee, there is more wisdom to glean from it.

Let’s look at it from the other direction: a significant number of people who received sham surgery showed pain relief from the procedure. They believed the surgery fixed their knee, and as a result, their pain lessened. The placebo didn’t magically fix their knee instead it opened the door for their central nervous to change how it interprets nerve signals.

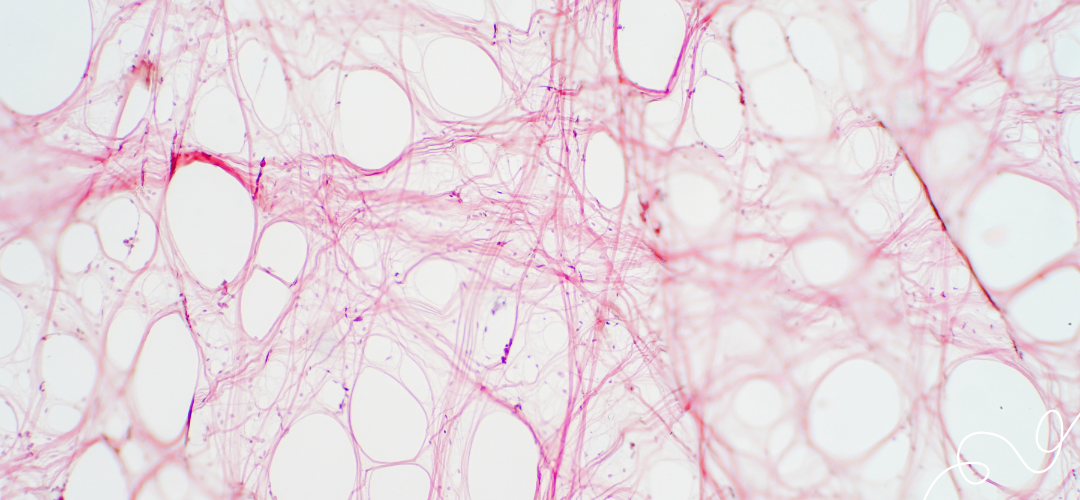

What is Fascia?

Can Myofascial Release Therapy Manipulate or Change Fascia Tissue?

A quick search may reveal that myofascial release can stretch and release fascia using sustained pressure. So, how much pressure is required to distort fascia?

“Our results indicate that compression and shear alone, within the normal physiologic range, cannot directly deform the dense tissue of fascia lata and plantar fascia, but these forces can impact softer tissue, such as superficial nasal fascia.” [4]

At first, the research reveals that a therapist could influence the fascia, specifically on the bridge of the nose. However, as we learn in the conclusion of the research paper, it describes the force required would be at the upper physiological limits of the human body.

“Our calculations reveal that the dense tissues of plantar fascia and fascia lata require very large forces—far outside the human physiologic range—to produce even 1% compression and 1% shear. However, softer tissues, such as superficial nasal fascia, deform under strong forces that may be at the upper bounds of physiologic limits.” [4]

Something I often say to my peers as a massage therapist is it doesn’t matter what is happening inside the body when we massage a client. Many of the modalities’ claims cannot be supported with scientific evidence anyway. At the core of every massage are three questions.

- Does it feel good?

- Is it safe?

- Is it ethical?

If the answer is yes to all three, then what does it matter what is happening on the inside of the body? If the client feels good, the techniques are safe, and your actions are ethical, everything else is fluff to the crunch.

According to the research, there is no evidence that myofascial release affects the fascia in any meaningful way, but it doesn’t matter. The goal of a massage is to help someone feel good.

Therapists have asked me in the past, “If you don’t believe in what myofascial release does, why do you practice it?” The techniques are spectacular; they feel good, add variety to the session, and are really effective at relieving pain.

Scars and Adhesions

Massage can be a tremendous benefit to the management of our health and wellness. I have used it in the management of pain, discomfort, and pruritus of my pneumonectomy scar. I used it to help manage the pain and anxiety resulting from cancer and chemotherapy.

“Treatment had a significant positive effect to influence pain, pigmentation, pliability, pruritus, surface area, and scar stiffness. Improvement of skin parameters (scar elasticity, thickness, regularity, color) was also noticed.” [8]

I love massage, but when we love something, we have a responsibility to be fair and honest about its abilities and limitations. When we read an article that supports the value and benefits of massage, we need to search for one that doesn’t. In life, we must avoid echo chambers that encourage bias so we may remain in the pursuit of truth.

Massage therapy has shown a moderately positive effect on pruritus, an unpleasant feeling of itchiness in the skin. Some studies have indicated that massage can effectively reduce scar thickening in hypertrophic (raised, thick, and abnormal scars) and burn scars, while other studies have shown no effect. One study indicates massage therapy significantly improves the pliability of burn scars. Other studies indicate massage has a moderate to strong effect on pain reduction in burn scars, while acknowledging the high risk of bias from the authors, which may have influenced the research results. [9]

Research has value, but anecdotal evidence is also important. Some massage therapists believe nothing has value unless a research paper has proven it. I am not one of these therapists. We don’t need a test to know the value of everything. At the core of massage, we are looking to feel good and manage our pain. We want to live our best days so we can treasure our time with the people we love.

Rethinking Assumptions

In my article “How do you get rid of muscle knots?” I discuss how massage therapists overemphasize the importance of palpable and perceived knots. We tend to touch something that feels different and quickly assume something must be wrong. The reality is that our bodies are asymmetrical; we don’t have the same shape on both sides. Sometimes, a bony landmark may sit slightly higher than the other side, or a muscle may be thicker. In other instances, we hallucinate a difference through palpatory pareidolia [10]. This phenomenon leads to false assessments and a tendency to search for the things wrong with the body instead of celebrating its uniqueness.

It is entirely within the realm of possibility that we can feel things within the fascia when we palpate the body with our hand. But this doesn’t mean every bump, lump, and physiological difference can or should be approached with myofascial release or other fascial-focused therapies. Just because you feel something, it doesn’t mean you know what it is, and just because it hurts when you touch it, it doesn’t mean it is a knot or a trigger point.

Other health conditions create scar tissue, including Axillary Web Syndrome (AWS). AWS is a condition that can occur after surgery or treatment for breast cancer, particularly after lymph node removal. It is characterized by the formation of tight, rope-like structures (cords) of scar tissue under the skin, usually extending from the armpit (axilla) down the inner arm and sometimes reaching as far as the forearm or hand. [11] Pain or tenderness can be experienced along the corded area, in addition to tightness or a pulling sensation, especially when lifting or stretching the arm. Individuals suffering from AWS may experience restricted range of motion in the shoulder or arm and swelling or discomfort in the affected limb. “Applying pressure to areas requires caution. Gentle manual techniques are recommended to avoid lymphedema or reddening of the skin.” [12]

It’s essential to question the assumption that every abnormality felt during palpation needs intervention. As massage therapists, fascia, adhesions, knots, and tight bands are so deeply ingrained into our training that it often leads to an overemphasis on perceived “problems” without fully understanding their nature or implications.

While it’s true that manual therapy allows us to feel differences in tissues, such findings do not automatically necessitate action, particularly when we consider conditions like Axillary Web Syndrome (AWS). AWS challenges this assumption because its scar tissue cords are not traditional fascial adhesions. Misinterpreting these cords as tight fascia or scar tissue to be aggressively broken up ignores AWS’s unique pathology and risks serious harm.

This highlights the importance of a deeper understanding of the body, the role of the nervous system, and the necessity for gentle, informed techniques when addressing conditions involving scar tissue or pain.

The Role of Myofascial Release and Gentle Therapies in Treating Axillary Web Syndrome

Research recommends Myofascial Release (MFR) as a manual treatment option for women with Axillary Web Syndrome. While MFR is generally considered a gentle therapy, the lack of standardization in the massage industry means that the term “MFR” encompasses a wide range of methods. There are over 30 fascial-focused therapies, many of which may define their methods as MFR. However, some of these therapies—such as Rolfing, Structural Integration, Muscle Adhesion Therapy, and certain forms of MFR—use firm or aggressive pressure that exceeds the level recommended for treating AWS.

Breaking Cords in AWS is Risky

One important thing to remember is the potential risks of trying to “break” the cords that develop with AWS. These cords are delicate and likely made up of inflamed lymphatic or venous tissues or fibrotic bands. Pushing too hard to release them could cause harm, especially since we don’t fully understand the long-term effects of doing so.

Unfortunately, many MFR practitioners focus on breaking up adhesions or scar tissue without realizing AWS exists. As a result, therapists might mistake the cords for tight fascia, working on them too aggressively and potentially making the problem worse or causing harm.

A Gentler Approach is Essential

Because AWS is fundamentally a disorder of the lymphatic system, gentler techniques are required to address its unique characteristics. Lymphatic Drainage Massage (LDM), for example, employs light, rhythmic pressure to promote lymphatic circulation and reduce swelling without aggravating the cords. Alternatively, therapists skilled in Indirect Myofascial Release—a form of fascial work that uses minimal force and respects the body’s natural release patterns—are better equipped to handle the needs of individuals with Axillary Web Syndrome.

- Breaking Adhesions is Not Always Wise:

- In the case of AWS, the cords should not be treated as traditional fascial adhesions. Overworking the area or aggressively attempting to release the cords can cause more harm than good.

- Many therapists lack the knowledge or training to distinguish AWS from other conditions and may unintentionally exacerbate the issue by using inappropriate techniques.

- Gentle and Informed Therapy is Critical:

- AWS requires careful treatment by a therapist who understands the condition and the importance of using gentle approaches like LDM or Indirect Myofascial Release.

- Evidence-based techniques should guide the treatment to ensure safety and effectiveness.

Conditions that May be Influenced by the Effects of Myofascial Release Therapy

Enjoy some research diving into Myofascial Release and various pathologies and conditions it may have an influence on.

Myofascial Release Therapy FAQ

Fascial Definitions

compartment syndrome involves the compression of nerves and blood vessels within a fascial compartment. This leads to impaired blood flow and muscle and nerve damage.

fasciotomy is a surgical incision or transection of fascia, often performed to release pressure in compartment syndrome. [1]

adhesions are bands of scar-like tissue that form between two surfaces inside the body. [1]

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is a group of inherited disorders of the connective tissue, occurring in at least ten types, based on clinical, genetic, and biochemical evidence, varying in severity from mild to lethal, and transmitted genetically as autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, or X-linked recessive traits. The major manifestations include hyperextensible skin and joints, easy bruisability, friability of tissues with bleeding and poor wound healing, calcified subcutaneous spheroids, and pseudotumors. Variably present in some types are cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, orthopedic, and ocular defects.

benign joint hypermobility syndrome is an alternate name for Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, type III, inherited as an autosomal dominant trait and characterized by hypermobility of the joints with minimal abnormalities of the skin. [1]

[1] Fascia Research Society. (n.d.). Fascia glossary of terms. Retrieved December 23, 2024, from https://www.fasciaresearchsociety.org/fascia_glossary_of_terms.php

[2] “Lynch, S. S. (2022, May). Placebos. In MSD Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved December 23, 2024, from https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/clinical-pharmacology/concepts-in-pharmacotherapy/placebos”

[3] Moseley, J. B., O’Malley, K., Petersen, N. J., Menke, T. J., Brody, B. A., Kuykendall, D. H., Hollingsworth, J. C., Ashton, C. M., & Wray, N. P. (2002). A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. New England Journal of Medicine, 347(2), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa013259

[4] Chaudhry, H., Schleip, R., Ji, Z., Bukiet, B., Maney, M., & Findley, T. W. (2008). Three-dimensional mathematical model for deformation of human fasciae in manual therapy. Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, 108(8), 379–390. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2008.108.8.379

[5] Active Release Techniques. (n.d.). Active Release Techniques. Retrieved December 24, 2024, from https://activerelease.com/

[6] Tri Natural Healthcare. (n.d.). The comprehensive guide to Active Release Technique (ART). Retrieved December 24, 2024, from https://trinaturalhealthcare.com/the-comprehensive-guide-to-active-release-technique-art/

[7] National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (n.d.). Abdominal adhesions. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved December 24, 2024, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/abdominal-adhesions

[8] Lubczyńska, A., Garncarczyk, A., & Wcisło‐Dziadecka, D. (2023). Effectiveness of various methods of manual scar therapy. Advances in Dermatology and Allergology, 40(2), 132-140. https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2023.124567

[9] Deflorin, C., Hohenauer, E., Stoop, R., van Daele, U., Clijsen, R., & Taeymans, J. (2020). Physical management of scar tissue: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4340. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124340

[10] Ingraham, P. (2015, September 17). Palpatory pareidolia & diagnosis by touch: Tactile illusions, wishful thinking, and the belief in advanced diagnostic palpation skills in massage and other touchy health care. PainScience. Retrieved December 24, 2024, from https://www.painscience.com/articles/palpatory-pareidolia.php

[11] Mayo, R. C. (2018). What the oncologist needs to know about axillary web syndrome. International Journal of Cancer and Clinical Research, 5(95). https://doi.org/10.23937/2378-3419/1410095

[12] Koehler, L. (n.d.). Axillary web syndrome. Lymphedema Blog. Retrieved December 24, 2024, from https://www.lymphedemablog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Axillary-Web-Syndrome.pdf